Safety in autosport

I find this article on web long time ago, and I save it on my computer together with a lot of other stuff. I don't remember author and I don't remember web page. I lost a couple of days looking for it so I can make a link to this page but I can't find it. If author of this page recognize his work, he can send me a mail and I will put a link to his page or remove this article if he wish so.

I apologize to him in advance!

All added pictures are from my archive and are not part of original site article.

The Full list of Formula 1drivers who died during some racing event is here.

During the 1960s the rate of fatal and serious injury within Formula 1 was 1 in every 8 crashes. Motor racing is dangerous. At every circuit there are signs warning of this, and it is usually printed on spectators' tickets.

Other sports carry risks; people die skiing and horse-riding, they perish while mountain-climbing and boating. Yet F1 was once so dangerous that the odds were against a driver retiring from the sport alive.

In this short series of articles, I want to look at some of the F1 fatalities that have occurred, and to see what measures have been put in place to prevent repetition.

The first part is about F1 fires, and I should caution readers that some of what follows makes distressing reading.

Fire

Parts of a racing car get extremely hot during the course of its normal use, and because that same car must contain highly flammable fuel, it is self-evident that a fire risk will be present.

Prior to 1963, there was nothing to stop a driver racing bare-headed in a T-shirt and shorts, but by the mid 1960's, the FIA had introduced regulations that required drivers to wear helmets and overalls as minimal protection.

The overalls of that era were nothing like the fire-resistant (for a limited time) suits drivers of today wear, and the helmets were of the visor-less peaked type.

There was some fire protection, but such precautions were not enough.

|

|

Lorenzo Bandini in his 12 cylinder Ferrari 1966 |

|

|

|

Lorenzo Bandini terrible fiery accident in 1967 |

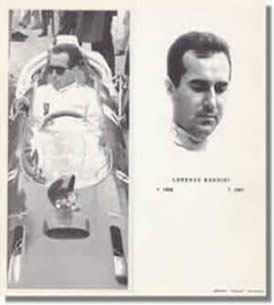

Lorenzo Bandini Obituary Card |

In 1967, Italian driver Lorenzo Bandini was running in second place at the Monaco Grand Prix when he crashed at the harbor chicane. His Ferrari car slid upside-down into the straw bales that lined the track, with Bandini trapped underneath it. The fuel tank was penetrated, and there was a fire. Situation was made worse by the fact that hay bales went up in flames too (hay bales were thereafter banned from Grand Prix racing).

Pulled at last from the wreckage, alive but horribly burned, Bandini was taken to hospital. He begged the doctors to let him die, but he lingered for three days before expiring.

|

|

|

|

In 1968 the French driver Jo Schlesser was given an opportunity to drive a Honda in the French Grand Prix at Rouen. Honda's John Surtees had already condemned the car, the RA302, as a potential death-trap.

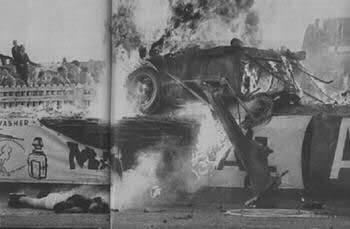

Schlesser crashed after two laps; the car and its almost-full fuel load burst into flames, and Schlesser perished in the inferno. As a result, Honda withdrew from F1 at the end of that season and did not return as a constructor for more than 30 years.

|

|

|

|

A member of the famous brewing dynasty, Piers Courage preferred to stay with Frank Williams into the 1970 season instead of accepting an offer from Ferrari. When Williams made the move into F1 in 1969, Courage came with him, and driving a Brabham he recorded two second-place finishes, at the Monaco and the US Grand Prix. He crashed fatally in Frank's F1 de Tomaso in the Dutch Grad Prix on June 21, 1970. He qualified in ninth, and running in the middle of the field, on the 23rd lap Courage front suspension or steering of De Tomaso's broke on the bump at Tunnel Oost, causing the car to suddenly go straight on instead of finishing flat-out bend. It then rode up an embankment and disintegrated, the engine break loose from the monocoque upon which it burst into flames (no automatic petrol seals at that time). To lighten the De Tomaso magnesium was used in its chassis and suspension. A racing car of that era was not constructed of carbon composites, but magnesium alloys were popular, and magnesium is a common ingredient of pyrotechnics and munitions.

The car's magnesium bodyshell burned so ferociously that nearby woods were set alight, hampering attempts to rescue him. It later emerged that Courage was probably already dead before the fire as he had been struck on the helmet by one of his loose tires. Both came rolling out of the cloud of dust at the same time.

Courage could not and did not survive; he was the first of F1's eight driver deaths of the 70's

Improvements

By the end of 1960s, the FIA had:

·banned straw bales from circuits,

·commenced their own circuit inspections;

·introduced electrical circuit breakers to reduce the risk of ignition after a crash;

·made recommendations (not obligatory) on fire-resistant clothing for drivers;

·brought in fuel tank safety bladders;

·mandated twin fire extinguisher systems; and

·specified that cockpits must be designed for fast evacuation.

It was not enough.

|

|

Roger Williamson (March), Zandvoort 1973 |

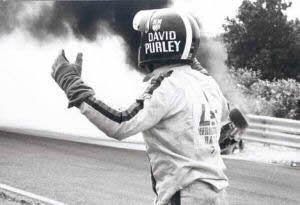

David Purley fight for his friend life with no help from other drivers |

In 1973, the English driver Roger Williamson was at the wheel of a March car in the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. After a sudden tire deflation or suspension problem, Williamson's car hit the barriers and slid upside-down in flames for about 300 metres before coming to a rest against the barriers on the other side of the track.

The race was televised, and I was among the millions who watched as true horror unfolded.

There were two fire marshals stationed at the corner where Williamson had crashed. Appallingly, they had only one fire extinguisher between them, and both were dressed in casual clothes, not in fire-resistant overalls.

The marshals were very wary of crossing the track, for the race was still in progress, but then Williamson's friend and fellow-driver David Purley stopped to help.

Purley grabbed the fire extinguisher from the marshals, and he tackled the flames. Williamson had not been seriously injured in the crash, and was conscious.

He shouted to Purley to get him out, and when the extinguisher was empty Purley tried to lift the car, but could not manage it on his own.

The marshals still would not approach the burning car, and now frantic spectators tried to break through the safety fence to assist Purley, but they were driven back by security men with dogs.

A full eight minutes after the crash, a fire truck arrived. Williamson was dead by then, and the heroic Purley was led away sobbing.

Throughout all that I have described the race continued, and Niki Lauda said afterwards that he was sick with shame that no other driver had stopped to help Purley.

There is a statue of Williamson at the Donnington Park race circuit. Purley died at age 40 when his Pitts Special aerobatic biplane crashed into the sea in 1985.

Here you can see a series of photos of Williamson tragic crash

Lauda: "I could see myself falling backwards into a black hole"

|

|

|

Lauda was not a fatality, I include him as a very famous-and courageous-F1 fire victim. Austrian driver Niki Lauda was reigning world champion when he started the German Grand Prix in a Ferrari at the Nürburgring in 1976. On the second lap, the car suffered a suspension failure and swerved into the path of Surtees-Ford car driven by Brett Lunger. |

|

|

Lauda's car burst into flames, and he was trapped in the wreckage. Luckily for him, several other drivers stopped to help, and he was swiftly extracted, but not before suffering very serious burns to his head.

A priest gave Lauda the last rites, but amazingly he recovered sufficiently to race again just six weeks later.

Lauda was left horribly scarred, but he only had reconstructive surgery to allow his eyelids to function, choosing to leave the rest of his head as the fire had ravaged it.

|

|

Gerhard Berger's crash at Tamburello corner during 1989 San Marino Grand Prix |

Jackie Ickx and Oliver crash at Servoz GP. Gavin is passing by. |

Further Improvements

There were a number of aspects for the FIA to look at that would improve F1 in-car fire safety. Measures were introduced to:

- Prevent fuel ignition

- safety foam in fuel tanks

- single fuel bladder mandatory

- Suppress a fire once started

- external handle to cut electrics and trigger extinguisher

- Protect the driver from any fire

- fire-resistant clothing, including hood and gloves

- Ensure the driver can quickly exit or be extricated from the car

- increased cockpit dimensions

- a seat which can be extracted with the driver in it in case of injury

- removable steering wheel

- Ensure swift response from circuit fire and rescue facilities

- at least five fire engines, crewed by four trained firemen, are on stand-by around the circuit

As long as there are racing cars with internal-combustion engines, fire will be an ever-present risk. It would be difficult to see how the FIA could improve driver fire safety from where it is at the moment, but we may be sure that the safety engineers will probably do just that.

In this second installment of the series, I will look at some of the F1 accidents in which drivers have died from causes other than fire, and at the safety measures introduced in response.

As with Part One, my starting point is the 1960's. Although F1 started in 1950, it was almost a different sport in the first decade because it included races such as the Indianapolis 500. Also, I have no personal memories of racing in the 1950's, and no records of FIA safety measures before 1963.

The 1960 Belgian Grand Prix at Spa was English driver Bristow's second F1 race. Driving a privately-entered Cooper, Bristow entered the Burnenville corner at about 120 mph and lost control.

At the side of the track was a waist-high embankment, which Bristow's Cooper impacted, and he was thrown from the car, over the embankment, and into the meadow beyond.

In the meadow, and only 10 feet from the track, there was a barbed-wire fence. Bristow hit the wire and was decapitated.

A few minutes later, Alan Stacey entered Burnenville.

Alan Stacey in his Lotus18 at Spa 1960

Another English driver, Stacey had an artificial leg, and used a motorcycle twist grip mounted on the gear lever to control engine speed.

Stacey entered the Burnenville corner not knowing that Chris Bristow lay dead and in two pieces in the meadow beyond. He would, though, certainly have known that Stirling Moss had been severely injured at Burnenville the previous day.

It was claimed by spectators that Stacey was struck in the face by a bird; certainly he lost control.

His Lotus climbed the embankment, plowed through a hedge, and landed in the meadow a few hundred yards from Bristow's remains. The driver was apparently killed instantly.

|

|

|

|

At the 1961 Italian Grand Prix at Monza, experienced German driver von Trips was involved in a collision with Jim Clark's Lotus. Von Trips' Ferrari spun, struck a barrier, and became airborne, throwing von Trips from the car and killing him.

The car then bounced back into Clark's Lotus before plowing into the crowd, killing 15 spectators.

Von Trips was very well placed to have become F1's first German champion, had he survived that Monza race. Jim Clark was to die in a Formula Two race in 1968.

|

|

Carel Godin de Beaufort's Porsche 718 after accident |

|

A wealthy and eccentric Dutchman, de Beaufort occasionally liked to drive barefoot and wore a Beatles wig instead of a helmet. He was too big a man to fit into contemporary racing cars, and competed in an old Porsche 718 as a private entrant.

In practice for the 1964 German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, de Beaufort's Porsche left the track at the Bergwerk corner. He was thrown from the car, and suffered massive head injuries, from which he died three days later.

Carel Godin de Beaufort's Porsche 718 was restored, and is displayed at the National Automobielmuseum in Leidschendam, Holland.

Commentary

Readers cannot fail to notice that the phrase 'thrown from the car' keeps cropping up in this grim account. When catapulted from a car, a driver would invariably suffer severe leg, back or head injuries because they would hit everything on the way out of the cockpit.

Hurtling through the air at speeds often well in excess of 100 mph, the driver would fall to earth with such force as to make his helmet almost an irrelevance.

The obvious answer was for drivers to wear seat belts.But the FIA's safety measures were not always supported by the sport's participants, and moves to make drivers wear seat belts were strongly resisted.

This writer can recall watching a 1960's TV interview with Graham Hill, in which the F1 champion argued that racing drivers could not wear seat belts because they relied on being thrown clear of the car.

Hill was of course referring to the risk of being trapped in a burning car, and he had certainly seen what an awful fate that was.The FIA's approach was to keep the driver in the car, protected from injury as much as possible, and to tackle fire as a separate issue.

In the face of driver opposition, mandatory wearing of seat belts was tardy, and the much safer six-point harness was not in F1 until the mid-1970's. Tragedy would not wait.

During the Italian Grand Prix at Monza in 1970, Rindt's Lotus T72 struck the barriers at the Parabolica curve. The barriers were too high to deflect the Lotus, and its nose passed under them.

Rindt was forced forward by the impact, and he slid under his lap strap, the buckle of which cut his throat. He was dead on arrival at hospital.

Jochen Rindt was posthumously awarded the F1 championship when Ferrari's Jacky Ickx failed to overhaul his points total.

|

|

|

|

The Tyrell team was having a successful 1973, with drivers Jackie Stewart and Francois Cevert scoring good points.

In practice for the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, Cevert's car touched the kerb in a tricky section known as The Bridge. The car spun and hit the safety barriers virtually head-on, uprooting and lifting them. Frenchman Cevert was cut in half by the barrier.

|

|

|

|

Austrian driver Helmut Koinig was killed at Watkins Glen in 1974 during the US Grand Prix.

After suffering a rear suspension failure, Koinig's Surtees-Ford crashed into the safety barrier, but at a relatively low speed.

The barrier, however, had been insecurely installed, and the bottom section gave way. Koinig's car passed underneath the top section, which decapitated him.

|

|

|

|

The 1978 Italian Grand Prix at Monza was the scene of Swedish driver Peterson's fatal accident. After a botched start, Peterson's Lotus was involved in a multiple collision with at least 10 other cars, including those of James Hunt and Riccardo Patrese. His car went into the barriers and caught fire.

Fellow drivers James Hunt, Clay Regazzoni, and Patrick Depailler pulled Peterson out of the car before he could suffer severe burns, but his legs were seriously injured.

Leg injuries should not have been fatal, but it took 20 minutes for the authorities to send medical assistance to the scene. Within 24 hours he was dead, as bone marrow had entered his bloodstream.

Peterson's wife Barbro never got over his death, and eventually committed suicide. She is buried alongside him.

For the rest of his short life, James Hunt blamed Riccardo Patrese for causing Peterson's accident, and when he was commenting on F1 races for the BBC he lost no opportunity to let viewers know about that.

Commentary

By the early 1980's, the FIA Safety Committee was really getting into its stride, and there was a commensurate reduction in fatalities. Some of the safety improvements were:

- The disgraceful matter of poorly designed and assembled barriers directly costing drivers' lives was resolved by rigourous FIA circuit inspections.

- FIA-approved helmets with shatter-proof visors became mandatory.

- Circuits were obliged to have a permanent medical centre with life support and resuscitation facilities.

- A fast rescue car was mandated.

- An FIA starter was appointed to end the shambolic starts that had contributed to some accidents.

- The concept of a reinforced survival cell was introduced, and extended to include the driver's feet.

The above list is only an extract. That they were effective improvements is evidenced by the fact that there were two driver deaths in the 1980's compared with eight in the 1970's.

|

|

|

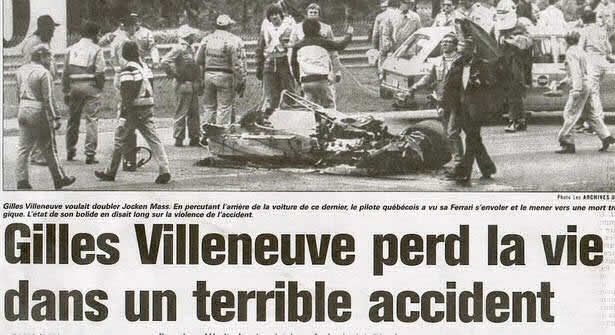

While qualifying for the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder in 1982, Villeneuve's Ferrari had contact with the rear of a RAM car driven by Jochen Mass. Villeneuve's car was launched into the air and fell outside the barrier onto an embankment; it then somersaulted alongside the track. The Ferrari disintegrated, and the driver's seat, with Villeneuve still strapped to it, was hurled across the track into some catch fencing. When the medical team arrived, Villeneuve was not breathing, and the Canadian was pronounced dead in hospital. |

|

|

Italian racer Riccardo Paletti had the shortest career of any F1 driver; he was killed on the start grid of his first race.

Just before the start of the 1982 Canadian Grand Prix in Montreal the Ferrari driver Didier Pironi stalled his engine.

When the race started there were a number of minor contacts as the field dodged around the stranded Ferrari, but in the chaos Paletti crashed into it at high speed in his Osella car, reportedly suffering chest injuries.

Medical staff were on the scene immediately, but as the FIA's chief doctor Sid Watkins was climbing onto the Osella the car's ruptured fuel tank ignited, engulfing it in a fireball.

The fire was very quickly knocked down, and thanks to his flame-retardant clothing Paletti had suffered no burns, but when Watkins reached him again, he was dead.

When the Austrian Roland Ratzenberger died in qualifying for the San Marino Grand Prix in 1994, he was the first F1 driver to perish during an event for 12 years. Driving for Simtek, Ratzenberger had only previously qualified for one F1 Grand Prix.

After a front wing broke off and jammed his steering, Ratzenberger was unable to turn into the Imola circuit's Villeneuve Corner, and he struck the wall there at high speed. The impact broke his neck.

Next day, during the drivers' race briefing, a new Grand Prix Drivers Association was formed to press for safety improvements. The GPDA's first directors were Michael Schumacher, Gerhard Berger, and Ayrton Senna.

So much has been written about the death of Ayrton Senna in a Williams car at the San Marino Grand Prix in 1994.

The precise cause or causes of the Brazilian's fatal crash have been the subject of investigation by the Italian authorities, who went so far as to bring charges against the Williams team. Many theories have been put forward, and I am not qualified to do so.

Whatever the cause, Senna's car left the track at the Tamburello turn at 193 mph and struck the concrete wall there at 135 mph.

The right front wheel with a suspension piece attached broke away in the impact, and hit Senna's head; his helmet was penetrated, and that caused the fatal injury.

Professor Sid Watkins performed a tracheotomy at the scene to try to get Senna breathing, but it was hopeless.

I will leave Ayrton Senna with Watkins' words:

"He looked serene. I raised his eyelids and it was clear from his pupils that he had a massive brain injury. We lifted him from the cockpit and laid him on the ground. As we did, he sighed and, although I am totally agnostic, I felt his soul departed at that moment."

Commentary

The two deaths at Imola in 1994 brought F1's safety standards under international scrutiny as never before. It is fair to say that the FIA rose to the challenge, I list just some of the changed or new requirements:

- Suspension must be designed to prevent contact of a front wheel with the driver's head in an accident by mean of adding the tether.

- At least 4 medical intervention cars, plus FIA Doctor car obligatory.

- Rear and lateral headrests to be one-piece, with standard quick-release method.

- Cockpit dimensions increased; side headrests extended to steering wheel.

- A seat which can be extracted with the driver in it in case of injury is mandatory.

- HANS (Head And Neck Safety) device mandatory.

- Main rollhoop must be able to withstand test load also from rear.

- Obligatory Confor padding beside and above driver's legs.

- Second, identical, tether and attachments for each wheel was mandated 2001 season.

Conclusion

The most enormous improvements have been made to safety in F1, and as I write this there has not been an driver fatality at an event since Ayrton Senna in 1994.

Yet the potential for tragedy is always present. At the 2007 Canadian Grand Prix the Polish driver Robert Kubica had an accident of such magnitude that it appeared he could not have survived.

Kubica was in fact virtually unscathed, but FIA safety engineer James Penrose was prompted to remark that "At some point, there will be a fatality again in Formula One."

Penrose was largely responsible for the introduction of the HANS (Head And Neck Safety) device, which probably saved Kubica's life by preventing his head being thrown about under the multiple forces of his accident.

He went on to hint at how he thought the next fatality might arise, in a cross-over crash, in which a car becomes airborne and passes over another car.

It is clear that no existing safety measure would save a driver's life if another car strikes his head.

If such an accident occurs, the next step is easy to foresee. It would not be possible to build up the head protection drivers currently have without further restricting their already poor visibility, so there would be a move to canopies such as are seen on jet fighters.

A canopy would raise escape and rescue issues, but engineering solutions to those already exist, and could be adapted to F1.

Perhaps the nature of F1 would be fundamentally changed; perhaps many fans would be outraged. But when it happens, remember you read it here first.

In this final installment of the series I will be looking at some of the F1 safety issues affecting marshals and spectators, and at measures designed to improve safety for those groups.

I started the first two parts of this series in the 1960's, but any look at F1 spectator safety really has to begin in 1955, when there was disaster at the Le Mans 24-hour race.

|

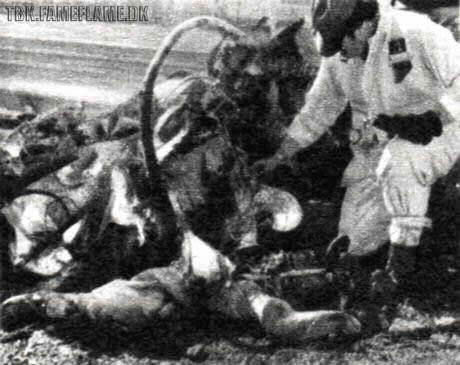

Linked images show a woman spectator's body smouldering near the wreckage of Levegh's car, and the scene of carnage in the spectator area. |

|

|

|

|

|

Motor racing's worst tragedy occurred partly because the competing teams did not have equal braking technology.

Mike Hawthorn was driving a Jaguar equipped with disc brakes, and when he slowed for a pit stop, the Austin Healey of Lance Macklin had to swerve to avoid him. He failed to notice that Pierre Levegh's Mercedes 300SLR was coming up behind.

Incredible as it seems now, Mercedes racing cars of that era did not have disc brakes; they had drum brakes and a flap that was raised behind the driver's head to slow the car through wind resistance.

Levegh's Mercedes rode up the sloping rear of the Austin Healey and was launched into the air. It stuck an earth mound at the side of the track, and then somersaulted for about 85 yards, disintegrating along the way; the engine, front axle, and bonnet (hood in American English) flew into the crowd with devastating effects.

The Mercedes' fuel tank burst, and there was a fire that ignited the magnesium alloy body, sending white-hot fragments into the crowd. Track staff tried to fight the fire with water, which only caused it to burn more fiercely.

When it was all over there, were 80 or more spectators dead from flying debris or fire; sources give differing numbers. Levegh had been thrown from the car when it somersaulted, and was killed when his head struck the ground.

The race continued while boy-scouts were collecting human body parts in sacks and priests were administering last rites. Mike Hawthorn was the winner.

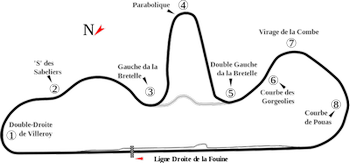

There is another consequence of this disaster. This year Motor racing has been banned in Switzerland. Before that the Swiss Formula 1 GP at Bremgarten, near Berne, had been a regular feature of the world championship. 1950 it was won by the Nino Farina, 1951 and 1954 races were won by Juan Manuel Fangio, 1952 Piero Taruffi and 1953 by Alberto Ascari. Since the ban, the only F1 world championship race called Swiss Grand Prix was held 1982 at Dijon-Prenois in France on August 29, 1982 (track on picture above, click for bigger), not far from the Swiss border. This was the only win of the season for eventual World Champion Keke Rosberg.

There is another consequence of this disaster. This year Motor racing has been banned in Switzerland. Before that the Swiss Formula 1 GP at Bremgarten, near Berne, had been a regular feature of the world championship. 1950 it was won by the Nino Farina, 1951 and 1954 races were won by Juan Manuel Fangio, 1952 Piero Taruffi and 1953 by Alberto Ascari. Since the ban, the only F1 world championship race called Swiss Grand Prix was held 1982 at Dijon-Prenois in France on August 29, 1982 (track on picture above, click for bigger), not far from the Swiss border. This was the only win of the season for eventual World Champion Keke Rosberg.

At the Italian Grand Prix in 2000, there was a multiple car accident involving several drivers. A wheel came flying from Heinz Harald Frenzten's car and struck fire marshal Paolo Gislimberti, fatally injuring him.

Gislimberti was behind the Armco but in front of the debris fence.

On lap five of the Grand Prix, Jacques Villeneuve's BAR-Honda launched itself off the back of Ralf Schumacher's car, spun backwards into the debris fence atop a concrete retaining wall. The fence did its job by keeping the car trackside but a second impact with the fence took place precisely at one of the narrow waist-high openings in the fence that allow marshals track access. The right-rear wheel on the BAR was 38cm wide and the opening was 40cm high. The force of the impact against a steel support post plucked the wheel from the car and somehow catapulted it through the gap. Graham Beveridge, a 51-year-old family man from Queensland, took full force of the wheel while standing in his appointed position.

On lap five of the Grand Prix, Jacques Villeneuve's BAR-Honda launched itself off the back of Ralf Schumacher's car, spun backwards into the debris fence atop a concrete retaining wall. The fence did its job by keeping the car trackside but a second impact with the fence took place precisely at one of the narrow waist-high openings in the fence that allow marshals track access. The right-rear wheel on the BAR was 38cm wide and the opening was 40cm high. The force of the impact against a steel support post plucked the wheel from the car and somehow catapulted it through the gap. Graham Beveridge, a 51-year-old family man from Queensland, took full force of the wheel while standing in his appointed position.

Despite the presence of medics at the scene, we knew nothing of the tragedy. It was not until the winner, Michael Schumacher, mentioned it in the post-race unilateral that we took on board the devastating news that a volunteer marshal had been killed.

|

Mark Robinson and his friend during Grand Prix du Canada 2013 |

Canadian Grand Prix marshal Mark Robinson has lost his life after being run over by a crane towards the end of Sunday’s Montreal race. The marshal was assisting in the retrieval of Esteban Gutierrez's Sauber car, which had hit a wall at Montreal's Gilles Villeneuve circuit, when he tripped and fell into the path of the mobile crane that was recovering the car to the pits. Crane operator could not see the man and drove over him. The FIA, Formula One's governing body, released a statement hours after the race saying the marshal, a member of the Notre Dame Automobile Club, had died in hospital from his injuries.

After Le Mans

After the last race of 1955, Mercedes withdrew from motor racing, and would not return for 32 years. The official inquiry into the disaster blamed inadequate track safety arrangements, and several countries banned the sport until improvements could be made; Switzerland's ban lasted until 2007.

1961 saw 11 spectators killed at the Italian Grand Prix in Monza when a Ferrari driven by Wolfgang von Trips cart wheeled into the crowd; von Trips was also killed.

When one looks at footage of F1 races in that era, it is readily apparent that there was nothing to stop such things from happening; there was no adequate separation of spectators from the track.Since the ghastliness at Le Mans and Monza, the main object of safety regulations pertaining to F1 spectators and marshals has been to prevent contact between those groups and any moving cars or car debris.

The means of accomplishing that objective have been separation by track design and security, distance, physical barriers, and car design.

After the deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna at May 1, 1994, in the San Marino Grand Prix immediate changes aimed at slowing the cars followed to make the sport safer. Engine sizes were cut, more demanding crash tests were introduced and circuit safety was pursued by the FIA with greater vigor. It was clear that drastic measures were needed to improve safety in Formula One.

1994 FIA began a campaign to improve safety in motor sport, which culminated in creating the FIA Institute for Motor Sport Safety.

Sweeping regulations changes characterized Mosley's time as FIA President. In 1994, he first banned electronic driver aids such as traction control and active suspension.

Mosley's first step in his campaign was to call upon the help of Professor Sidney Watkins, MD, FRCS, commonly known as Professor Sid, world-renowned neurosurgeon who served twenty-six years as the FIA Formula One Safety Delegate and Medical Delegate. Watkins had been working in Formula One since 1978, when Bernie Ecclestone, then the owner of the Brabham team and the boss of the Formula One Constructors Association, offered him the job to be the championship's and racetrack doctor, head of the Formula One on-track medical team, and first responder in case of a crash. It is testament to the continual efforts of Professor Watkins that there has not been a serious accident in Formula One in over ten years. Much of this is due to the research and action on safety led by Watkins as president of the FIA Institute for Motor Sport Safety. His forthright approach and no-nonsense attitude had already made him a respected figure in Formula One circles. His work in motor sport and safety has been so valued that, in 2002, he was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE).

Check my article about improvement in driver safety year by year.

In 2001 alone, we saw an Australian marshal's fatality in the Australian GP; Dale Earnhardt's death in NASCAR; Michele Alboreto's death while testing his Audi Le Mans sports car; Alex Zanardi's massive leg injuries in a recent CART race.

The common factor in all these accidents was the high speed of at least one car involved (each over 300 kmh). At these speeds, the energy involved is very high and the cars are often capable of flying, thereby avoiding the energy dissipation systems installed at the circuits. Recent accidents are also at the end of straights (where drivers overtake) and composite wings or suspension components are most highly stressed

Some of the most important safety features in Formula 1 are now being built alongside the track. Generous run-off zones help reduce the speed of a car that has come off the track, while tire stacks covered with rubber belt absorb the impact energy of the car when hit. Istanbul is now considered the most advanced track

The FIA studies track design with a view to reducing the risk of accidents, and also to determine the areas that spectators should be excluded from. Computer simulations are used to identify circuit configurations most likely to prove dangerous, such as high-speed turns with a decreasing radius.

Many track changes have resulted from that work. However, this is not a foolproof science, because it is possible for an accident to occur at any point of the track; the Le Mans accident occurred on the pit straight.

There was never a fence that some fool did not want to climb over, and never a prohibited area that someone did not feel compelled to intrude upon. That is where security staff come into play, to intercept those who would endanger themselves or others. Check my article about improvement in track safety year by year.

Distance is said to lend enchantment. Certainly it is intuitive logic than the further a person is from the scene of an accident, the safer they should be from calamitous consequences. Any small piece of flying debris will rapidly be slowed by air resistance, and at the same time gravity will be drawing it earthwards.

Since 1970, the FIA has specified that track verges must be a minimum of 3 metres, and spectators must be a minimum of 3 metres behind debris fencing, restrained there by another fence. In practice, spectators are usually not so close to the track, the foreshortening effect of the TV cameras fools us in this regard.

There are two main types of barriers to protect spectators. Armco guardrails are designed to keep cars on the circuit, and debris fences are meant to keep flying pieces of wreckage away from spectators.

Temporary circuits, such as Melbourne, are allowed a different specification of debris fence to those installed at permanent circuits such as Spa Franchorchamps; usually the temporary fence will be lower.

Other types of barriers have been used. Straw bales were once common, but they were banned in 1970. Concrete walls instead of Armco have been allowed since 1984, but the catch fences that previously existed at some circuits were banned in 1985.

Tyre walls are still in use as a supplement to Armco, mainly to provide a softer impact on run-off areas, but the FIA have recommended that they be covered with conveyor belt material to prevent cars becoming partially buried, as we saw happen to Kovalainen at the 2008 Spanish Grand Prix.

FIA recommendations usually become requirements, so we can expect further news on this subject.

In the past, there have been gruesome fatalities inflicted on drivers by poorly designed/placed/installed Armco barriers, but the FIA's circuit specifications and inspections have put an end to such things.

For those who share my deep and abiding fascination with trivia, ARMCO is the acronym for American Rolling Mill Company, a US steel maker. Other companies produce corrugated steel safety barriers, but the word Armco has become generic.

The main aspect of car design that affects spectator and marshal safety is the endeavour to prevent parts from flying off in an accident. Wheels are the chief hazard, for in this age of carbon composites, body sections are too lightweight to become dangerous missiles.

In 1998, the FIA mandated that F1 car wheels and tires must be attached to the chassis by tethers fastened at one end to the wheel hub and at the other end to the chassis. The tethers are made of a polymer called Zylon, and will take a 5000kg load. They lose strength if twisted, however, such as can happen when suspension parts break in the course of an accident.

Zylon is degraded by light, so the tethers are encased in an opaque shrink-wrap and thus cannot be visually inspected. Teams replace them every couple of races as a precaution against them having suffered damage.

The FIA mandated two tethers per wheel for the 2001 season, but in the opening race in Melbourne, marshal Graham Beveridge was killed by a wheel from Jacques Villeneuve's car. It was reported that Beveridge was standing at a gap in the debris fence.

Since then we have seen accidents where the wheel tethers have performed well, and we have seen other examples where they have failed. Further developments can be anticipated

More controversial changes came in 1998 with the advent of the grooved tire and narrow tire track regulations. By regulation, the tires feature a minimum of 4 grooves with the intention to provide less grip and to slowing the cars down. They can be no wider than 355 mm and 380 mm at the front and rear respectively.

The new millennium brought greater restrictions with safety and cost restriction in mind, with engines required to last first for two and then for four races, then cut in capacity to 2.4 litre V8s and frozen in specification.

Check my article about improvement in racing car safety year by year

Being a fire marshal is a voluntary job that means long days standing out in the open, whatever the weather. There is no shortage of volunteers though, and in fact, people spend years marshalling at minor events before they get the chance to join the F1 elite.

The nature of their responsibilities means that fire marshals have to be stationed close to the track, which makes them vulnerable, and they must also be prepared to intervene after an accident. Sometimes their services will be needed on the opposite side of the track to their station, and then the serious hazard of crossing the track arises.

At the South African Grand Prix in 1977 Renzo Zorzi's Shadow car had an engine failure, and he parked it at the side of the track. It was not a dangerous position, and Zorzi was unfastening his helmet in a fairly leisurely manner when flames erupted.

Zorzi then leapt from the cockpit, but did not forget to trigger the on-board extinguishers as he did so. He was in no danger, but two fire marshals ran across the track to assist.

One of the marshals, Frederik Van Vuuren, was struck by a Shadow driven by Zorzi's teammate Tom Pryce. Van Vuuren was killed instantly, his body split apart by the impact, and the fire extinguisher he had been carrying hit Pryce on the head, killing him also.

This was one of the most bizarre tragedies ever to afflict F1; somehow a small fire that put no life in danger had cost two lives.

Tom Pryce's helmet was basic and old, probably 10 years old. When impacted by the fire extinguisher it was ripped from the driver's head, pulling the chinstrap into his throat and almost decapitating him.

After Pryce's death, it was mandated that only FIA-approved helmets could be worn by drivers, and helmet specifications have become ever more stringent since then.

One cannot be sure that any helmet would have saved Pryce's life, for the kinetic energy of a 4kg fire extinguisher struck at 160mph is enormous, equivalent to a bullet from an extremely powerful rifle.

Only a small part of that energy was absorbed by killing Pryce, there was enough left to knock the rollbar off his Shadow, and then to send the extinguisher flying clear over the grandstand. It landed in a car-park beyond.

The deaths of Tom Pryce and Frederik Van Vuuren illustrate how impossible it is to ensure total safety at an F1 event. Marshals must be present, and must have the discretion to venture onto the track when it appears necessary.

We know that there was no need for Vuuren to cross the track, but he did not know it, and he was just 19 years old and probably following his older companion.

Since that terrible day at Kyalami, the FIA has tightened up considerably on the training marshals must undergo. As well as being licensed by their national motorsport authority, they must now also be licensed by the FIA.

This series has not been a comprehensive history of F1 safety advances, such an undertaking would be beyond my resources.

The FIA's efforts to improve spectator safety have been outstandingly successful, as they have been with driver safety, so much so that if you attend a Grand Prix, you are more at risk of tragic mishap during the journey than from any incident during the event.

I would like to conclude by paying tribute to all those who have worked so hard at improving safety, just as I pay my respects to those who have lost their lives.

Nice read from unknown author. Thank you!

SEAS

In my opinion, Formula 1 was very lucky between 1986 and 1994 that there hasn't been any fatalities during F1 race. It was only because of pure luck, they'd been lucky. Only after Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna death things starts to go more scientific. I think that is the reason why since 1994, there hasn't been a fatality, because of the changes that were made.

|

|

Martin Brundle1984 Monaco grand prix |

Martin Brundle1984 Monaco grand prix |

|

|

Martin Brundle again |

Depailler in Hockenheim 1986 |

|

|

Gilles Villeneuve at Japanese GP at Fuji 1977 |

|

|

|

|

|

Piquet crush at Indy 500 year 2002 |

Tom Pryce crush at Kyalami 1976 |

|

|

At the 2007 Canadian Grand Prix Kubica had a serious crash approaching the hairpin on lap 27, in which his car made contact with Jarno Trulli's Toyota, and hit a hump in the grass which lifted the car's nose into the air and left him unable to brake or steer. The car then rolled as it came back across the track, striking the wall on the outside of the hairpin and coming to rest on its side. The speed measured when his car clipped the barrier was 300.13 km/h (186.49 mph), at a 75 degree angle, subjecting Kubica to an average deceleration of 28 g. After data from the onboard accident data recorder had been analyzed it was found that he had been subjected to a peak G-force of 75 g!!! After two races brake he was back in car. And next year, 2008, he win for first time on same racing track while driving for the same team.

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

Kubica's Kanada GP 2007 big crush. After 2 missed races he was back behind the wheel, and next year he won in Canada |

|||

The Full list of Formula 1drivers who died during some racing event is here.

Check my article about improvement in racing car safety year by year

Check my article about improvement in track safety year by year

Check my article about improvement in driver safety year by year