Keel

Suspension design on Formula 1 has been seemingly stagnant the last few years. Double Wishbone A-Arm suspension has been the norm. The suspension arms have been made out of carbon fiber for many years. Carbon fiber suspensions maintain little flexure, which is important for predicting the response of the car as it travels over undulating surfaces. Traditional old style low nose cone designs allow the lower suspension arms to be directly attached to the main structural parts of the car.

Suspension design on Formula 1 has been seemingly stagnant the last few years. Double Wishbone A-Arm suspension has been the norm. The suspension arms have been made out of carbon fiber for many years. Carbon fiber suspensions maintain little flexure, which is important for predicting the response of the car as it travels over undulating surfaces. Traditional old style low nose cone designs allow the lower suspension arms to be directly attached to the main structural parts of the car.

However, since the move to high nose cone designs - which allow better use of airflow underneath the car, and to a improved efficiency of the front wing - location of these lower arms has proven problematic.

For ideal suspension geometry, and maximum mechanical grip, the lower arms should be long and near parallel with the road. As there is no longer any structural bodywork in these low positions, extensions were developed to allow the suspension to be mounted with correct geometry.

Tyrell 019 and Tyrell 019 B pioneered high nose design

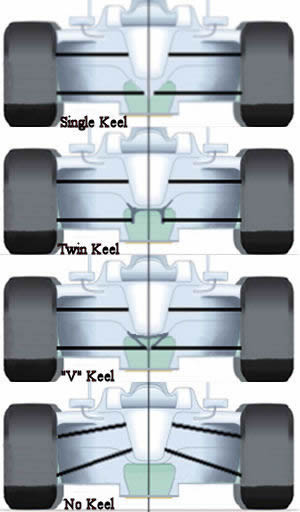

Since the advent of high nose designs in the early 1990s, pioneered on the Tyrrell 019 Formula One car, three major keel designs have emerged to solve this problem:

Single keel

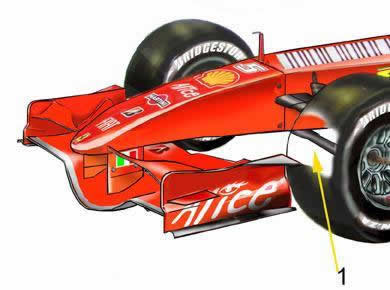

The original and most simple solution was to place a single keel below the nose cone that the suspension could be attached to. Below the nose cone is fitted a protruding plate where the lower suspension arms are attached. The single keel design has a couple of advantages. It is a simple design with an ample surface allowing an F1 designer to play with the placement of the arms to get maximum from their suspension and maximum mechanical grip. The one big flaw is that the keel disrupts air flow below the nose cone. If you go to all the trouble of raising the nose to increase front wing downforce, the last thing you want is something disrupting the aerodynamics and negating the downforce advantage. Ferrari has stuck with the "Single-keel" design until year 2007, and has had considerable success.

Twin keel

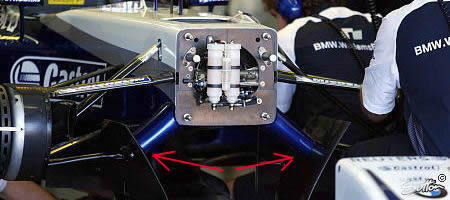

Extreme twin keel design by BMW

Extreme twin keel design by BMW

Second solution is what is called the twin keel design. As the name suggests, a twin keel design has not one but two plates protruding from the bottom of the nose on which the suspension arms are attached. The twin-keel concept was conceived by Harvey Postlethwaite in year 2000, during his time at Honda Racing Developments. The twin-keel made its racing debut in Formula One the year after that, on the Sauber car, where it was introduced by designer Sergio Rinland. Adrian Newey adopted the "Twin keel" feature in 2002 on the McLaren MP4-17.

The keels are on the edge of the nose sides, and protrude less than the single keel design (well, in most cases, check 2002 Arows design in picture below, used again 2006 by Super Aguri). A twin keel adds to the engineering complexity of the suspension and also is heavier. Because of flexing problems, engineers have to reinforce pylons (keels), and that make them to heavy. Although it improves the airflow below the nose the suspension set-up is compromised (it is a lot heavier) and it is harder to make post-design suspension adjustments. However, the aero benefits outweighed these concerns and in the early part of this decade nearly all teams were running some variation of the twin keel design (with exception of Ferrari).

Teams continued to innovate around the twin keel design. McLaren or BMW (picture above), for instance, elected to have the keel protruding outwards to improve airflow.

|

Super Auguri team started their racing history 2006 on Bahrain GP with 4 years old Arrows A23 F1 racer. With Takuma Sato and Yuji Ide behind the wheel. |

V-keel

Only Renault and Red Bull BR2 2006 adopted a V-keel concept. This was a hybrid between a single and twin keel with the two plates emerging from the bottom edge of the nose before touching in a V shape. They believed this make-up allowed greater suspension flexibility, more mechanical grip with little cost to the car's aero package. Benefits include a reduction in disturbance to the underbody airflow in comparison to a single-keel design, with fewer geometry, flexing and weight restrictions than that with twin-keels. Thinking is that V-keel suspension fixing point is stiffer than in case of single keel because of angled supports.

Only Renault and Red Bull BR2 2006 adopted a V-keel concept. This was a hybrid between a single and twin keel with the two plates emerging from the bottom edge of the nose before touching in a V shape. They believed this make-up allowed greater suspension flexibility, more mechanical grip with little cost to the car's aero package. Benefits include a reduction in disturbance to the underbody airflow in comparison to a single-keel design, with fewer geometry, flexing and weight restrictions than that with twin-keels. Thinking is that V-keel suspension fixing point is stiffer than in case of single keel because of angled supports.

This concept also allowed a more or less free passage of the air after front wing.

It seems that a lot of publications are convinced the V-keel has the same aero benefit as No-keel. But that is not possible because there is some disruption in air flow trough V-structure.

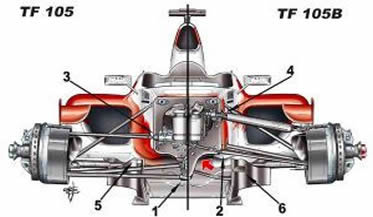

Zero keel

The most recent innovation has been the introduction of zero keel designs, where, you won't be surprised to hear, there is no keel. One limitation of any keel design is that, while the keel influence may vary, the suspension linkages themselves still disrupt the underbody airflow. In "Zero keel" design, the suspension is mounted directly on to the body of the car. This came about largely because of FIA regulation changes that mandated teams to place the front wing in a more elevated position. This reduced the downforce available at the front of the car. This meant that in order to maximize downforce, designers decided to move to a zero keel suspension arrangement to maximally free airflow, believing that taking a penalty on mechanical grip was better than any loss in aero efficiency.

As the nose cone is in a raised position, this mean that the suspension arms take a distinctly inclined angle with respect to the road surface, reducing suspension efficiency.

The zero keel design has become regular in F1. Last year (2007), all teams ran such a design except Red Bull, who behind the brains of Adrian Newey elected for a twin keel layout. Renault insisted on sticking to their V-keel solution, until year 2008 when they changed to zero keel configuration.

Difference in suspension position between single and zero keel