Red Bull Racing Flexible front wings

Season 2011

Moveable aerodynamics had been made illegal in 1969, but in 1972 the 72D was fitted with a rubber bush on the rear wing's mount to allow it to change its angle at high speed. In the pits a mechanic or scrutineer was able to put all his weight on it without the wing moving, but under the high aerodynamic loads on a long straight the angle of the whole wing changed and reduced drag. The wing avoided detection until McLaren's Denny Hulme spotted Fittipaldi's helmet appearing above the wing on long straights. At the risk of being rumbled, Lotus removed the rubber bush and no further action was taken.

Since the past season's Australian GP I started to note that the front wings in the RedBull's seemed to bend and it sometimes even touched the ground and created some sparks. Estimates suggest that the front-wing endplates are deflecting by up to 24mm. This was later confirmed by McLaren's plead to investigate the Red Bull's front wings and the FIA changing the wing deflection test from using a 50 kg load and a 10 mm deflection, to a bigger 100 kg load and a 20 mm being allowed.

But why if they pass the test, their wing still bends? Easy, carbon fibre can be weaved in a certain way to behave differently under different loads. The theory is that the wing flexes outwards and down due to a sophisticated layering process of the carbon composite material.

Bristol University's Aerospace Engineering department provides further details, explaining that:

Bristol University's Aerospace Engineering department provides further details, explaining that:

"Laminated composite materials designed adequately can present elastic coupling properties that can be used to induce an adaptive change. For instance, a composite presenting in-plane elastic coupling that is loaded under normal loads experiences a shear deformation. The proposed morphing design consists of a wing made of laminated composite materials presenting elastic couplings so as to induce twist when the wing bends. This concept, if proven, could provide a passive actuation for the control of the wing twist."

But why we want front wing to twist and bend?

Front wing ground effect is the key. To understand it we must know that principal point is that front-wing ground-effect depends upon two mechanisms: firstly, as the wing gets closer to the ground, a type of venturi effect occurs, accelerating the air between the ground and the wing to generate greater downforce. Secondly, a vortex forms underneath the end of the wing, close to the junction between the wing and the endplate, and this both produces downforce and keeps the boundary layer of the wing attached at a higher angle-of-attack. In this regime, the downforce increases exponentially as the height of the wing is reduced. Beneath a certain critical height, however, the strength of the vortex reduces. Beneath this height, the downforce will continue to increase due to the venturi effect, but the rate of increase will be more linear. Eventually, at a very low height above the ground, the vortex bursts, the boundary layer separates from the suction surface, and the downforce actually reduces. That's in perfect conditions. However, the presence of a rotating wheel immediately behind the wing makes things a little more difficult!

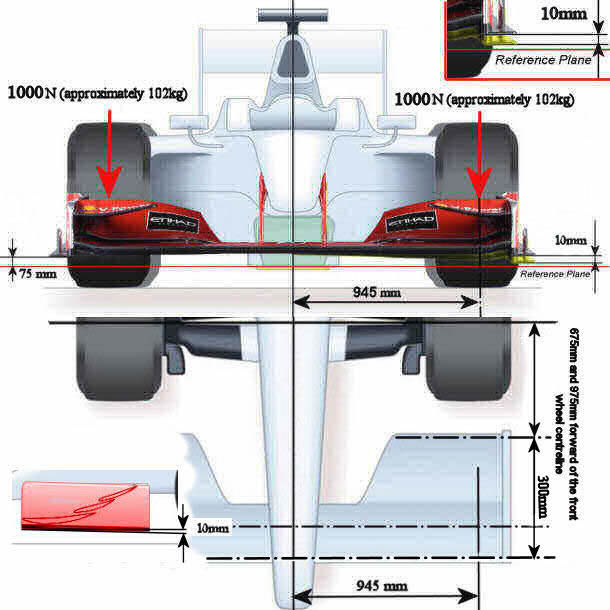

The technical regulations state that a front wing must be no lower than 75mm above the reference plane, which is the lowest point of the car excluding the plank. To check compliance with this rule, 1000N (approximately 102kg) loads are applied to the two ends of the front wing in scrutineering on the distance of 790 mm from the car centre line and 800mm forward of the centre line of the front wheels. Movement of no more than 20 mm (10 mm from 2013) is allowed. This year the FIA have brought into force a stricter test in which loads are applied either simultaneously or on one side at a time.

The technical regulations state that a front wing must be no lower than 75mm above the reference plane, which is the lowest point of the car excluding the plank. To check compliance with this rule, 1000N (approximately 102kg) loads are applied to the two ends of the front wing in scrutineering on the distance of 790 mm from the car centre line and 800mm forward of the centre line of the front wheels. Movement of no more than 20 mm (10 mm from 2013) is allowed. This year the FIA have brought into force a stricter test in which loads are applied either simultaneously or on one side at a time.

The 1000N (approximately 102kg) test remains the one in force in 2011, and although this is the best the FIA can do due to the strength of the wing at the point of testing, it is woefully ineffective. By rule of thumb, an F1 car's front wing produces approximately 35% of the total downforce of an F1 car and with cars nowadays producing over 2,000 kg of downforce, front wings are subject to a massive load of almost 7,000 Newtons (700 kg).

|

For season 2013, FIA will overhaul testing procedures for front wings, introducing a more-comprehensive and strenuous series of tests designed to root out the practice of exploiting flexible bodywork regulations. Front wings in particular will be subjected to revised parameters, with a tolerance of just 10 mm (0.39 in) permitted when the wing is subjected to a load of 1000N (102 kg). There is nothing in the rules about rotation of the wing so the FIA has moved the point of application of the load test from a load at one point roughly on the centre line of the wing, to loads at two points, one towards the front and one towards the back to try to ensure it catches any wings moving in that way. The wings are allowed to deflect just 10mm. Aware of the possibility that some teams could be using designs that passed the old tests but still rotated at high speed, the FIA tweaked its testing so that the area being tested is now in an area 150mm further out, 945 mm from the car centre line and at any point along a 300mm section of the endplate (at points 675mm and 975mm forward from the front wheel centreline). This new test should ensure that any attempt by teams to utilise the rotating wing principle would be exposed. |

Despite controversy about their 'flexible' front wing, Red Bull have passed this test, leaving their rivals striving to develop similar solutions.

Of course, realising the desired front-wing performance not only requires the development of special type of simulation technology, but also understanding of how to implement the requisite elasticity via the orientation of the carbon-fibre plies. Number of rival teams have been caught out in terms of front wing development because they believed the tougher 2011 tests would rule out the idea of a flexible wing working. Because the test changed over the winter, teams did not put any effort into that side of things. But Red Bull have demonstrated that you can take an approach that is perfectly legal and gain advantage from it.

After all FIA tests performed on RBR front wing, there was no question about Red Bull Racing's legality, and that the only options going forward is for either even more stringent FIA tests to tighten up that area of car design, or for rival outfits to copy it.

From Autosport:

Gary Anderson:

Red Bull Racing Flexible front wings explained

Flexible front wings; the one single thing that most F1 teams think is key to Red Bull's current aerodynamic advantage. But there's a little bit more to it than that.

The science

The key to creating overall car downforce is to manage the way air separates around the front wing. This component is the first to influence the air flow and if this is badly managed, the rest of the car will suffer. This becomes easier the closer the wing runs to the track surface as it is basically running in what is called 'ground effect.' This not to be confused with WIG (Wing In Ground Effect)

Of course, the FIA mandates a minimum wing height relative to the underneath of the chassis and it also applies a load versus deflection test to eliminate any serious deflection. But if a team can make its wing flex as much is permitted when subjected to the kind of aerodynamic load that speed creates, it can make the wing sit lower and therefore manage the air separation more efficiently. This is what helps you create that extra downforce.

What Red Bull has done better than anybody else is to stop this process adversely affecting the rest of the car, and in particular, the outboard area in front of the front tires.

If you don't manage the airflow separation in this area, the downforce becomes inconsistent and if your front wing is 'ridged' this causes the complete car to bounce up and down.

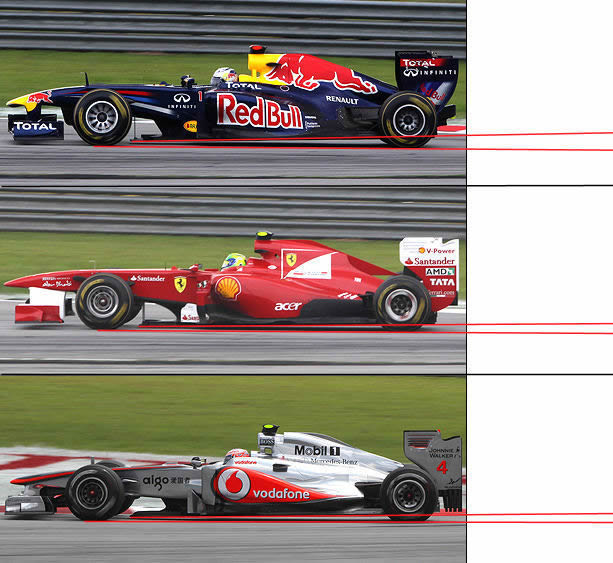

As the wing gets lower to the ground, the airflow separates (from the wing) and the downforce is reduced. The car rises up, the wing re-attaches, and more downforce is created, which sucks the car back towards the ground. This phenomenon is called 'porpoising', and the McLaren has been quite noticeable in doing this during 2010 and 2011.

The wing

If you say that aerodynamics determines 90 per cent of a car's performance, then the front wing is 60 or 70 per cent of the 90, and that's because it's the part that hits the air first and dictates how it flows over the rest of the car.

If your front wing creates a turbulent wake or poor vortex generation, then every component you develop downstream of the front wing is optimized to work in that environment.

However, if the wake is good, then the downstream aerodynamic surfaces can be made to work harder and the complete package will than create more overall downforce.

Development of any racing car starts at the front and sweeps through to the rear; change the front wing configuration and you might not see any improvement until you optimize the rest of the car around it and that is why there is no quick remedy if a team is off the pace.

The execution

Red Bull has optimized carbon fibre technology by a very clever means. Carbon fibre is a bit like rope, the more load you want it to withstand, the thicker the piece you use. Carbon fibre comes in many forms and can be layered up any way you want. Lay it out in straight lines, and it's tremendously strong in terms of tension; lay it out at an angle to the load path, and, despite it being the same strength, it will flex under a given load.

Getting the lay-up just right to allow you to pass the FIA load to deflection test, but yet still increase the deflection as the load increases with speed is no easy task. But it is possible and that is why the teams employ high-priced boffins to come up with solutions to this type of problem.

It's not something that's exclusive to Red Bull either; everybody's wings flex, it's just to make it flex in the way you want and in what extent that they flex that is the bone of contention here.

The rake argument

|

|

Red Bull car stationary |

Red Bull car at speed |

If you studied a photo of a Red Bull or another car side by side in China 2011, you'd see that the front wing of the Red Bull appeared to be much closer to the ground. While rivals say that this was as a result of excessive flexing, Red Bull argues that this is down to the rake of the car, i.e. that the RB7 has approximately the same front ride height as everyone else, but that the rear of the car is run much higher in order to maximise aero efficiency, thus creating a rake shape. This means that the front wing looks lower to the ground as it is ahead of the front axle.

|

We can easily see that the RB7 is in fact running a high rake angle. The rear end of the car is much higher than the front end. |

The rake itself is fundamental to a car's aerodynamic specification. With a car that's higher at the rear, the aerodynamic centre of pressure can be further forward at lower speeds, which will help reduce low-speed understeer. As the car speeds up, the rear will lower itself and if the diffuser works correctly then the centre of pressure will move rearward, making the car more stable in fast corners.

The optimum rake will vary from circuit to circuit, but in my experience, by having a rake change ratio of less than 3:1 (in other words, if the front suspension compresses around 10mm, the rear should compress around 30mm), then the car will not perform as well as it potentially could and you could only counter-act that by running your car stiffer and sacrificing a bit of mechanical grip and suspension compliance.

If the front ride height of both the Red Bull and the McLaren were, for example, 25mm, and Red Bull ran a 75mm rear ride height compared to a McLaren 50mm rear ride height, that would give it a 25mm difference in rake.

Considering that the wheelbase is around the three-metre mark and that the front wing leading edge is about one meter in front of the front wheel centre line, this means the front wing of the Red Bull will start life about 8mm lower than the McLaren.

As the principle outlined suggest, this will create more front downforce at low speed.

If a Red Bull is running a 3:1 stiffness ratio and a McLaren – because of its lower rear ride height – is running a 2:1 stiffness ratio, then at high speed the front wing will end up at approximately more or less the same height. Other than that, Red Bull has better boffins than McLaren and in optimizing the wing lay-up they have an advantage all the way through the speed range.

The art of copying

|

|

Red Bull car on the track at speed |

Red Bull car in the pits |

It won't be easy for rival teams to copy Red Bull's wing and just find a few tenths of a second straight away. I guarantee that if you put a Red Bull front wing on any other F1 car in a wind tunnel, it would be worse than that team's current configuration.

That's because it's not just the wing that makes the Red Bull the best car aerodynamically, it's the whole aero philosophy of the car, with everything working in sync with each other.

Designers and engineers are intelligent enough to know this, and I believe that this is the reason why nobody has tried to copy Red Bull so far.

The solution

All the FIA tests have proved that the Red Bull front wing is totally legal, despite what rival teams believe. As long as this continues to be the case, it's time for the other teams to stop bitching about it and just accept that Red Bull has done a much better job than them.