Brakes

The beginning of this article will be a bit boring, but is important to discus all of this to be able to understand the brakes!

Brakes are designed to slow down your vehicle but probably not by the means that you think. The common misconception is that brakes squeeze against a drum or disc, and the pressure of the squeezing action is what slows you down. But this is only a small part of the reason you slow down.

Brakes are essentially a mechanism to change energy types. When you're travelling at speed, your vehicle has kinetic energy. When you apply the brakes, the pads or shoes that press against the brake drum or rotor convert kinetic energy into thermal energy via friction between disc and brake pads. The cooling of the brakes dissipates the heat and the vehicle slows down, and in order to brakes to work whell this dissipation of the heat must be good and fast. This is all to do with The First Law of Thermodynamics, sometimes known as the Law of Conservation of Energy. This states that energy cannot be created nor destroyed, it can only be converted from one form to another. In the case of brakes, it is converted from kinetic energy to thermal energy.

Because of the configuration of the brake pads and rotor in a disc brake, the location and Angular force of the point of contact where the friction is generated also provides a mechanical moment to resist the turning motion of the rotor.

If you drive a car long way down the hill, you're probably familiar with the term brake fade which is used to describe what happens to brakes when they get too hot. By the First Law of Thermodynamics, as you start to come down the hill, the brakes on your vehicle heat up, slowing you down. But if you keep using the brakes, the drums or discs and brake pads will stay hot and get no chance to cool off. The next time you try to brake, because the brake components are already so hot, they cannot absorb much more heat.

In every brake pad there is the friction material which is held together with some sort of resin. Once brake pads starts to get too hot, the resin holding the pad material together starts to vaporize, forming a gas. That gas has to have somewhere to go, because it can't stay between the pad and the rotor, so it forms a thin layer between the two trying to escape. The result is very similar to aquaplaning while going too fast in the rain; the pads lose contact with the rotor, thus reducing the amount of friction. This is a brake fade.

As the brake components cool down, their ability to absorb heat returns, the pads cool off which means they have more chance to heat up again before the resin vaporizes, hence the next time you use the brakes, they seem to work just fine.

This type of brake fade was more common in older vehicles. Newer vehicles tend to have less outgassing from the brake pad compounds but they still suffer brake fade. Why? Well it is again to do with the pads getting too hot. With newer brake pad compounds where outgassing isn't so much of a problem, the pads transfer heat into the calipers because the rotors are already too hot and the brake fluid starts to boil as a result. As this happens, bubbles form in the brake fluid. Air is compressible, brake fluid isn't, so you can put your foot on the brake pedal and get full travel but have no braking effect at the other end. This is because you're now compressing the gas bubbles and not actually forcing the pads against the rotors. Brake fade again.

So how do the engineers design brakes to reduce or eliminate brake fade? For older vehicles, you give that vaporized gas somewhere to go. For newer vehicles, you find some way to cool the rotors off more effectively. Either way you end up with cross-drilled, grooved or vented brake rotors. While grooving the surface may reduce the specific heat capacity of the rotor, its effect is negligible. The rotors will heat up to cool down no faster or slower. However, under heavy braking once everything is hot and the resin is vaporizing, the grooves give the gas somewhere to go, so the pad can continue to contact the rotor, allowing friction and allowing you to stop.

How does it apply to bigger brake rotors; a common sports car upgrade? Well sports cars and race bikes typically have much bigger discs or rotors than your average family saloon car. The reason again is to do with heat and friction. A bigger rotor has more material in it so it can absorb more heat. More material also means a larger surface area, which as well meaning more area for the pads to generate friction with, also translates to better heat dissipation. On top of that, the larger rotors mean that the brake pads make contact further away from the axle of rotation. This provides a larger leverage and mechanical advantage to resist the turning of the rotor itself.

That explains the whole principle behind why bigger rotors = better stopping power.

Taking it one step further, carbon or ceramic brake rotors, as found on high-end Ferraris, Porshes or McLaren F1 road cars, and Formula-1 race cars, are even better again at heat transfer.

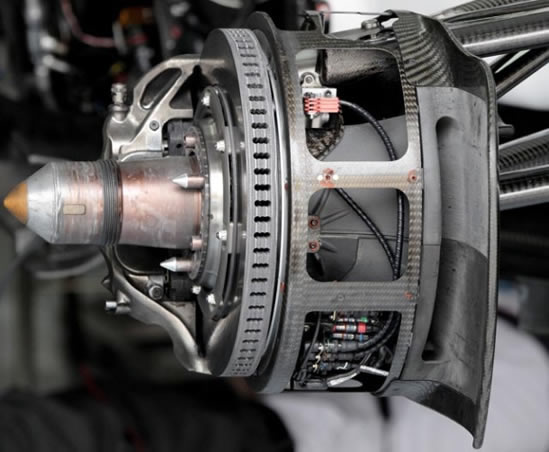

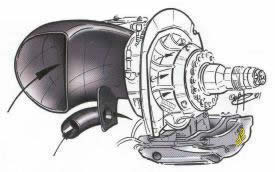

The whole understanding of the conversion of energy is critical in understanding how and why brakes do what they do, and why they are designed like they are. In Formula 1 car, you'll see the front wheels have huge scoops inside the wheel pointing to the front. This is to duct air to the brake rotors to help them cool off because in Formula 1 racing, the brakes are used viciously every few seconds and spend a lot of their time trying to stay cool. Without some form of cooling assistance, the brakes would be fine for the first few corners but then would fade and become near useless by half way around the track. Another reason for this scoops in F1 case is that rotors are working on very high temperature of around 800-1000 C, and without additional venting this heat will be transferred to wheels and tires with negative effect to stability of metal and rubber.

BTW, first production car to use disc brakes on front wheels (on any wheels actualy) was Citroen DS19. Together with two braking circuits, it was a class of its own.

An important note about drilled rotors (www.carbibles.com):

Drilled rotors are typically only found (and to be used on) race cars. The drilling weakens the rotors and typically results in micro fractures to the rotor. On race cars this isn't a problem - the brakes are changed after each race or weekend. But on a road car, this can eventually lead to brake rotor failure - not what you want. I only mention this because of a lot of performance suppliers will supply you with drilled rotors for street cars without mentioning this little fact.

|

|

To be quick in terms of lap time, you need to be good at stopping. It sounds odd but it's true. At some venues almost a quarter of the lap is spent pushing on the brake pedal.

Unsurprisingly, both Monaco and Singapore require the most use from the brake pedal, with 23% of their respective laps spent under braking. The Hungaroring is the next with 22%, while Mexico and Shanghai both require 21% of the driver's time to be spent using the brakes. Spa and Monza require the least amount of time on braking, requiring just 12% each of the lap spent under braking. As a result, Monza requires the most effort from the brakes, sustaining an average deceleration of 5.5g – almost 0.9g higher than Sochi, the next most demanding circuit. The peak deceleration of the season was that produced at the final chicane at Montreal at 5.6g. Based on data released last year by Brembo, the maximum deceleration in Montreal is on the particulary demanding braking zone for the hairpin.

Of the seven braking points in Montreal, the most critical is braking zone into the final right/left chicane that exits by the "wall of champions". Cars hit the brakes at around 322km/h and brake for 1.6s to slow to around 148km/h. This takes only 49 metres, with 5.6g deceleration and a force on the brake pedal of 161kg. The Turn 8 right/left chicane requires cars to slow from around 297km/h in 47 metres and 1.62s, at 4.8g deceleration with 160kg force on the pedal. The hairpin at Turn 10 is the best overtaking opportunity, with a 63 metre braking zone to go from 292km/h to around 68km.h in 2.44s.

Each Formula 1 team uses around 10 sets of brake calipers per season, as well as 140-240 brake discs and 280-480 pads.

In particular, the Parabolica creates a maximum deceleration of 6.6g, where the driver exerts a maximum load of 232kg on the brake pedal to reduce the overall stopping distances. (Data released by Italian brake manufacturer Brembo for year 2017.)

Disc brakes are an order of magnitude better at stopping vehicles than drum brakes, which is why you'll find disc brakes on the front of almost every car and motorbike built today. Sportier vehicles with higher speeds need better brakes to slow them down, so you'll likely see disc brakes on the rear of those too.

Formula 1 use disc brakes. They consist of a rotor and caliper at each wheel. Expensive carbon-carbon (the same material used on the Space Shuttle) composite rotors - introduced by the Brabham team in 1976 - are used instead of steel or cast iron because of their superior frictional, thermal, and anti-warping properties, as well as significant weight savings. Strangely ceramic discs have not been a development seen at races. Rules limit the diameter and thickness of discs, but no other regulatory restrictions are placed on these parts.

These brakes are designed and manufactured to work in extreme temperatures, up to 1,000 degrees Celsius, but carbon brake discs work properly at between 300 and 800 degrees Celsius. Below that they don't have any stopping power; above it and the wear rate of the carbon increases dramatically with temperature.

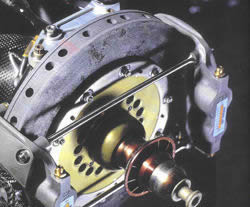

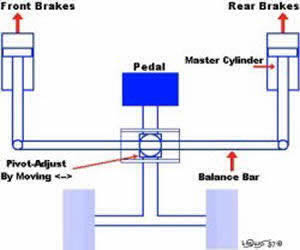

Formula 1 cars and indeed all race cars, have two independent brake circuits (front and rear) which come together at the brake pedal. A pivot on the pedal apportions pedal load to the twin master cylinders, according to the position of the pivot on the crossbar that links the pedal to the master cylinder pistons.

Brake balance or brake bias is controlled from F1 cockpit, controls on steering wheel. Stronger front brake balance causes the front of the car to dip more than the back, that is, more weight transfers to the front wheels.

Apart from having greater stopping power, it allows better tire contact to allow the car to steer into the corner while under brakes. Stronger rear brake balance, will cause the rear wheels to lockup slightly (dependant on how strong you set balance) when the weight transfers to front during braking. Causing slight oversteer. Not a bad thing, because you might want to induce a bit of oversteer in heavily understeering cars. Too much front brake bias and the front tires will lockup, causing severe understeer, which isn't good. And too much rear brakes can cause the back to lockup causing severe oversteer and spin.

As you can see there is a cause and effect for each setting. Too much or too little of a setting will cause undesired effects. Too much front brakes and the tires lock causing understeer. Too little, and the car doesn't stop fast enough, causing the car to continue its momentum straight ahead.

An average F1 car can decelerate from 100-0 km/h in about 17 meters, compared with a 2007 Porsche 911 Turbo which takes 31.4 meters.

When braking from higher speeds, aerodynamic drag enables tremendous deceleration: 3.5 g to 4.0 g (44.1 to 49 m/s2), and up to 5.5 g at the high-speed circuits such as the Autodromo Nazionale Monza (Italian GP). This contrasts with 1.0 g to 1.5 g for the best sports cars (the Bugatti Veyron is claimed to be able to break at 1.3 g). An F1 car can brake from 200 km/h to a complete stop just 2.9 seconds, using only 65 meters.

There are three companies who manufacture brakes for Formula One. They are Hitco, (based in the US, part of the SGL Carbon Group), Brembo in Italy and Carbone Industrie (part of Messier Bugatti) from France. Whilst Hitco manufacture their own carbon/carbon, Brembo sources theirs from Honeywell, and Carbone Industrie purchases their carbon from Messier Bugatti.

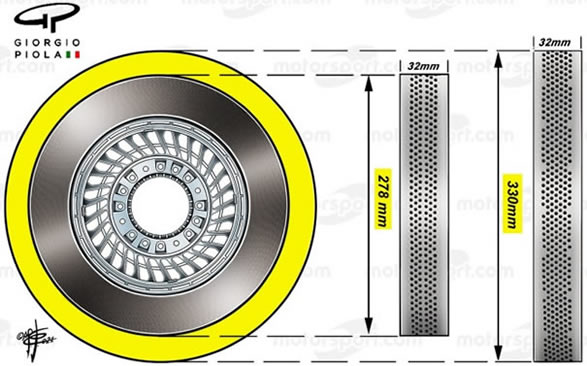

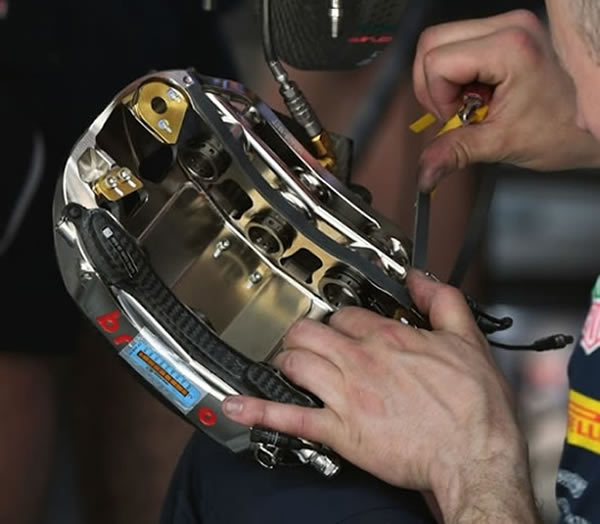

In 1998, the FIA introduced rules restricting the brake system to calipers with a maximum of six pistons and no more than two pads. The maximum brake disc diameter was set at 278mm, and maximum thickness at 28 mm. But after big aero regulation changes 2017, and because of higher speed, the widening of the cars and, in particular, the wider tires that increased mechanical grip and loads maximum thickness was changed to 32mm. Also, brake pad thickness was changed from 6 to 8mm. The front carbon/carbon brake pads are actuated by 6-piston opposed calipers provided by AP Racing or Brembo. But at the rear the discs are smaller by up to 12mm and some teams are using four pistons calipers.

The calipers are aluminum-lithium alloy bodied with titanium pistons weighting approximately 2 kilograms and costing well over 7000$ a piece. The regulation limits the modulus of the caliper material to prevent teams using exotic, high specific stiffness materials. Titanium pistons save weight, but also have a low thermal conductivity, reducing the heat flow into the brake fluid.

The manufacture of brake friction material begins with same basic fibre as that used in the production of the carbon fibre fabric from which racecar chassis are made – PAN (polyacrylonitrile). It is, however, processed in a wholly different way, being passed through carbon deposition and high-temperature oxidation stages lasting several weeks that transform its molecular structure and result in a material that as well as offering lower weight relative to metal brakes provides greater durability and higher thermal capacity. These gains were not without cost though, and a long development was necessary to provide sufficient cooling of the discs, pads and calipers and other parts in their vicinity before the use of carbon brakes became practicable.

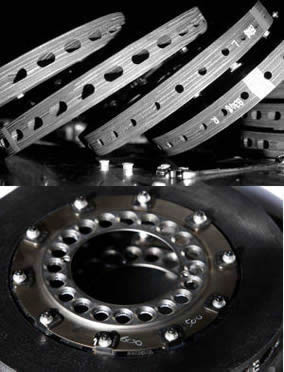

Disc and pad material varies according to their manufacturer. It is also tuned for each race track and even for each driver. Additionally cooling patterns will vary from track to track. In Melbourne or Hungary, for example, we can see the high density drillings across the disc. With Melbourne or Hungary being heavy on braking the pads are also drilled in attempt to keep the brake system cool. The number of ventilation holes increased over the years, from a 30 holes twenty years ago, to 100-hole disc to 1200 for the 32mm discs. On the picture, Brembo brake discs evolution from 2005 to 2015.

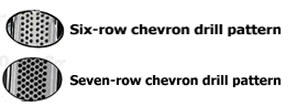

At the 2018 Mexican Grand Prix Ferrari became the first Formula 1 team to run a new  generation of "Brembo" brake discs featuring seven distinct rows of holes in chevron patern to reach the magical unprecedented 1400 holes disc to help cooling.

generation of "Brembo" brake discs featuring seven distinct rows of holes in chevron patern to reach the magical unprecedented 1400 holes disc to help cooling.

It's a breakthrough that was first made possible when the regulations were changed in 2017 to allow teams to run discs that are 32mm wide, rather than 28mm. This extra space was enough for Brembo to increase its cooling capacity quite significantly.

The unique high-altitude demands of Mexico city, where teams struggle to keep temperatures of engines and brakes under control, was the perfect proving ground for the new disc that will be made available to all customers in 2019. F1's brake suppliers have long balanced out increasing the number of holes to help cooling with the need for structural integrity of the disc itself.

Major progress has been made in brake disc material, and Brembo, which supplies multiple F1 teams including Ferrari, has been among those at the forefront of development. In 2013, Brembo introduced the new CER material to replace the old CCR type, which offered gains in terms of performance and wear and reduced maximum wear of 4-5mm on the hardest tracks to around 1mm.

|

|

|

|

Examples of few differently drilled brake discs ventilation holes . Top left picture shows Ferrari flat directionaly drilled holes. Holes point from outside directly to center of the disc. The holes are formed of three holes merged into one. Same situation is with Red Bull Racing disc brake on picture top right. Different logic show Mercedes with disc drilled with 4 rows of smaller holes drilled directionaly. Marusia, on picture down right, use two rows of bigger holes drilled tangentially. Number of holes in 2017 was risen to approximately 1300 holes. Pictures from scarbsf1 blog By Craig Scarborough. |

|

Brakes and pads wear at an equal rate, so the few millimeters gap in between disc surface and drillings is all the wear these parts will see, before catastrophic failure. As wear increases with temperature there are sensors measuring the disc surface temperature and also wear sensors for both the inner and outer pads.

To monitor all the functions on the brakes, there will be an array of sensors fitted to the parts (visible at picture below). On upper picture you can see 3 round connectors on RedBull front brake caliper. These are all connected back to the main ECU, rather than cabling for each sensor passing through the wishbones to the cars main wiring loom, there is a hub fitted to the upright that collects all he signals and passes them back via a single cable. This Hub Interface Unit (HIU) is a common part supplied by MES to all the teams. It has inputs from the aforementioned Pad wear and disc temperatures sensors, as well as two wheel speed sensor (two in case one fails), also a load cell for measuring pushrod (or pullrod) loads.

- 4 seconds is the amount of time it takes for a Formula One car to go from 300km/h to a complete stop.

- At 200 km/h, a Formula One car requires just 2.9 seconds to stop completely, in only 65 meters.

- At 100km/h, these values are incredible: 1.4 seconds and 17 meters!

Under these heavy braking periods, a driver is subjected to a horizontal deceleration of close to 5,2G. - Brake disc is made of carbon/carbon composite, and working temperature is over 1000°C during braking.

- At Albert Park (Australian GP), during second corner braking, Formula 1 can develop 4,6g of load and developed power of 1855 Kw (1,855Mw).

"The use of carbon-fibre brakes requires a little time to get used to," states Jarno Trulli. "In fact, during the first milliseconds after pressing the brake-pedal; it feels like nothing is happening." This delay is in fact the length of time required by the disk/caliper tandem to reach operating temperature, which increases by 100°C per tenth of a second for the first half-second of braking, after which it can reach up to 1200°C. After that short period, deceleration is immediate, and brutal.

Used carbon brakes and brake pads

With the introduction of the current Energy Recovery Systems technology in 2014, F1 adopted brake-by-wire technology for the rear brakes thanks to the demands of harvesting energy from them. Check out my article about new Formula 1 Brake by Wire brake system.

As part of the 2021 revamp of F1, one of the key changes is size of the wheels. For decades, F1 cars have run on 13-inch wheels now joining much of the rest of the racing world as it adopts 18-inch wheels and new, low-profile racing rubber.

The limit on wheel size was enacted as a way to stop teams from fitting ever-bigger brakes to the cars; a lot of overtaking happens in the braking zones, and a consequence of reduced stopping distances is that overtaking becomes much harder.

Move to much more road-relevant 18-inch wheels, alowed technitian to fitt biger brake discs. The brake discs (330mm up from 278mm) and the brake drum itself will increase in size to accommodate the introduction of the 18" wheel rims and the larger well they create.

As an aside, all teams will be supplied the 18" wheel rims by BBS in 2022, as the company won the tender to become F1's standard supplier.